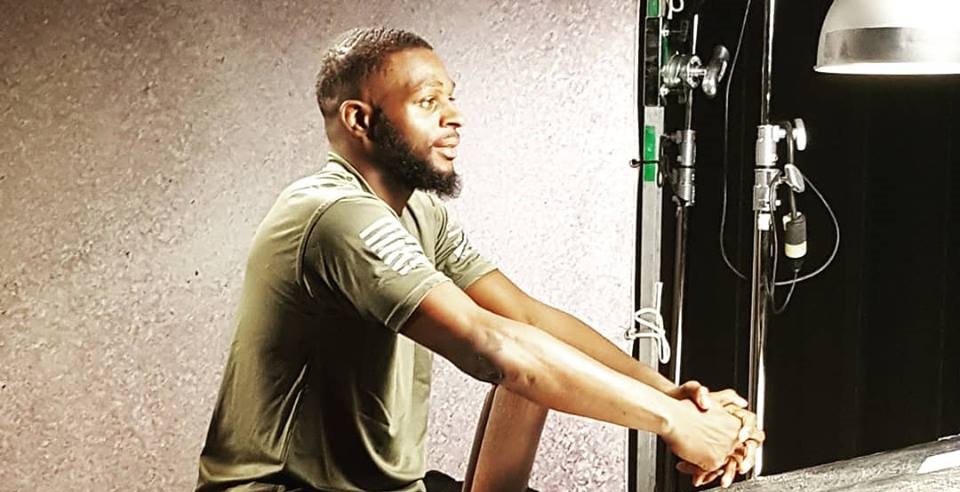

From statistic to success story: How Montel Jackson changed everything around

Who Montel Jackson was supposed to be is completely different from who he is today. Growing up on the north side of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, there were only a few things Jackson was expected to do with his life, and the options before him were grim.

For a while, Jackson believed he was going to have to choose between those options, which were death or incarceration. Everyone around him met the same fate, and it continued to happen no matter how hard they fought to avoid it, so Jackson began to go down that same path. As unfortunate as it sounds, this was the reality many African American males, especially in their youth, faced and still face today.

Jackson found himself in the epicenter of it all, hanging around mostly in an area that lived up to the notorious reputation it received after being recognized as the “the ZIP code that incarcerates the highest percentage of black men in America”. Seeing people getting arrested constantly was nothing surprising or shocking to Jackson. At that point, it was a way of life.

“For me, it’ll probably be a little worse than that because the area I lived in [was bad],” Jackson told MyMMANews. “I lived in the meadows, but my favorite aunt lived on 23rd and Keefe and that’s right inside the 53206-area code. It’s one of the area codes with the most incarcerations in the United States. Almost all the residents are usually in jail or on some type of parole or probation, so I would hang out there. If you talk about what the statistics are there, they said that I was either going to be in jail or dead. I got pictures with friends and I’m the only one that is alive from those pictures. I’m the only person that’s not dead or in jail. I’m the only person that did something.

“Everybody thought I was going to be in jail or dead,” said Jackson. “By the time I turned 21 or 22, that was the kind of expectation people had on my life, so for anyone to say anything [about me], it doesn’t even matter. Because according to the same people, I wasn’t supposed to be here. I was supposed to be in jail or dead. I was supposed to have four or five kids and three or four f**king baby mommas. All types of stupid sh*t.”

Where he comes from, those stereotypes were often repeated to people like Jackson. It took him some time to realize that those choices he was initially given were not the only ones he had.

Eventually, Jackson made the choice to get involved in sports. And his decision allowed him to look at things in a totally new perspective because the people he met and grew close with due to his involvement in sports helped him see that what he was used to was not normal by any means. Jackson admits he became desensitized to his environment, which made him work twice as hard to change that and look for better of himself.

Jackson excelled in wrestling and hoped to use it as a way to turn his life around from where it was headed. In a matter of years, Jackson has done just that and is one of the most well-known prospects competing against some of the world’s best in the bantamweight division of the UFC.

Having accomplished what was once considered the unthinkable, Jackson uses his story to inspire those who are in the same situation he was in. He still resides in the very area of Milwaukee that he grew up in for various reasons, but one of the most important ones is so that he can give back to the youth of the community through coaching.

Jackson thanks his own mentor and former coach, Roger Quindel, for getting him involved.

“I never really thought about the stuff he was telling me,” said Jackson. “He was always like, ‘Montel, you have to be the person you needed when you were a kid. You have a responsibility. You owe it to yourself and you owe it to the kids.’ Roger would always tell us its not about the money. It’s about giving back. It’s about ensuring the future of the next generation. So, the more I started to coach and come back every summer and start training the smaller kids, I started to think about how these kids really look up to me. Whenever I go back, I get a hero’s welcome because they understand that it’s not too many people that look like me or them that actually makes it out and goes on to be successful.

“It makes me feel weird sometimes. I didn’t know that wanting to be the best and working hard makes you a hero. To me, it doesn’t. It’s just doing what you do best. But to other people, it’s inspiring, so I guess in their eyes it makes you a hero.”

The kids from City Kids Wrestling really look up to Jackson, who is a welcome change from the kind of role model they had grown accustom to in the area. Jackson did not want them to look up to the same people he did when he was younger because he knows what that would lead to.

“When I was a kid, you know who I looked up to? You know who my heroes were? People don’t understand, kids want to be what they see. So, if you’re seeing the same thing reciprocated to you every day, then most likely you’re going to be that. You’re going to inspire yourself to be that. So, who I wanted to be like? I wanted to be like the neighborhood drug dealers. They had everything to me. They had money. They had cars. They had the clothes. They had the women. They had the prestige. They just had this ambiance about themselves that was mythical. Who don’t want to be like that? Who doesn’t want to feel like some beloved person?”

Part of his coaching method is to speak about his journey in life and how it can be learned from. As much as Jackson dislikes speaking about his upbringing in public, he does it with the kids because he seems a little of himself in each of them.

“I talk to them about it because they can relate to it. Some of them are still having the same choices [as I did] right now where they are living at, so they can relate to it. And they know they can ask anybody on the street and find out that what Montel is telling them is real. You can go to my neighborhood and they will tell you that dude was a piece of work, but he turned it around. He’s doing good now.

“Remember, it’s more to black people than pain and trauma,” said Jackson. “It’s always the same stories, but we have better stories than that. People need something to believe in. They find inspiration in other people’s stories. If a person can see my story and they can draw inspiration from it, then I’m fine.”