Parametric Thinking: How to Train Your Design Mindset for Complex Problems

Design projects rarely stay stable from start to finish. Requirements shift, constraints evolve, and new inputs appear along the way. Approaches built around fixed decisions often struggle once conditions begin to change.

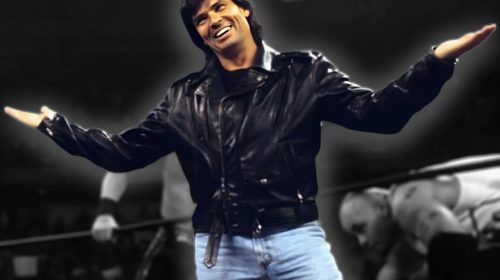

Many systems outside architecture already work with this reality. Online platforms adjust rules based on user behavior and ongoing feedback. In spaces focused on blonde women dating online, results improve when preferences and matches can evolve instead of staying locked in. This adaptive logic points toward a different way of approaching complex design problems.

What Parametric Thinking Really Means

Parametric thinking focuses on relationships instead of objects. A design no longer exists as a single resolved form but as a set of rules that respond to inputs. Parameters define what can change, what must stay stable, and how each variable influences the system as a whole.

This approach separates intent from appearance. The designer defines logic first and lets form emerge through interaction between constraints. Control shifts from drawing shapes to shaping behavior. Outcomes vary, yet coherence remains because every result follows the same internal logic.

Why Traditional Design Thinking Breaks Down With Complexity

Linear design methods perform well under stable conditions. Complex systems expose their limits.

Linear Processes vs. Non-Linear Problems

Traditional workflows assume cause and effect move in one direction. Complex problems resist that structure.

- Decisions influence multiple outcomes at once.

- Small changes create disproportionate effects.

- Feedback alters the system after each adjustment.

- Dependencies multiply across scales.

Linear methods hide these interactions until late stages, when changes cost more and clarity fades.

The Cost of Late Design Decisions

Fixed decisions early in a project feel efficient. They reduce ambiguity and create visible progress. Complexity punishes that confidence. Late-stage discoveries force redesign, compromise performance, or inflate budgets. Parametric thinking keeps decisions adjustable, which protects projects from late surprises.

Scaling Issues in Large or Data-Driven Projects

Large systems amplify small errors. Urban plans, façade systems, or data-informed environments expose weaknesses in rigid logic. A single assumption can propagate across thousands of elements. Parametric systems absorb scale more gracefully because rules adapt across repetition.

Core Mental Shifts Behind Parametric Thinking

A mindset shift matters more than any tool. Parametric thinking asks designers to rethink what success looks like.

Designing Systems Instead of Solutions

A system produces outcomes over time. A solution addresses one moment. Parametric thinking prioritizes systems because they stay useful as conditions change. This shift alters how design intent gets defined and controlled.

Key characteristics of system-driven design include:

- Rules replace fixed dimensions.

- Relationships define structure.

- Variation stays intentional.

- Adaptability becomes measurable.

- Control moves upstream into logic.

These traits allow designers to explore options without losing coherence. Decisions stay adjustable while the underlying structure remains stable. That balance supports complexity without sacrificing clarity.

Embracing Variation as a Feature

Uniformity once signaled precision. Parametric thinking values controlled variation. Multiple outcomes reveal how a system behaves under different conditions. Variation exposes strengths and weaknesses early, which improves decisions before commitment.

Constraints as Creative Drivers

Limits sharpen design intelligence. Constraints define the space where meaningful solutions exist. Parametric systems treat constraints as active inputs instead of obstacles. Climate, structure, cost, and performance inform form continuously rather than interrupting it.

How to Train a Parametric Design Mindset

Training this mindset requires practice, not memorization. Small exercises reshape habits over time.

Start With Questions, Not Forms

Early focus on appearance locks thinking too soon. Better questions guide stronger systems. What must change? What must remain stable? What influences what? Clear questions define useful parameters before form enters the discussion.

Think in Inputs and Feedback Loops

Every system reacts. Inputs produce outcomes. Outcomes influence future inputs. Parametric thinking stays aware of that loop. Designs improve when feedback informs each iteration instead of arriving as criticism after completion.

Practice Abstracting Design Logic

Abstraction strips a design down to intent. Geometry, materials, and scale step back. Logic steps forward. This practice clarifies relationships and exposes unnecessary complexity. Strong abstraction supports flexible outcomes later.

Learn to Delay Aesthetic Decisions

Aesthetic confidence grows from structural clarity. Early visual decisions often mask weak logic. Parametric workflows delay those decisions until systems prove resilient. Visual quality improves when logic carries the load first.

Common Mental Traps Beginners Fall Into

Early mistakes often come from habits carried over from linear design methods. These patterns feel efficient at first but create friction once systems grow more complex:

- Tool-centered thinking: Software mastery feels productive, yet tools do not create parametric thinking. Logic precedes interface. Systems fail when thinking follows the tool instead of guiding it.

- Over-parameterization: Too many variables reduce clarity. Every parameter should serve intent. Excess choice complicates control and hides cause-and-effect relationships.

- Fear of ambiguity: Uncertainty feels uncomfortable. Parametric thinking requires tolerance for unresolved outcomes during exploration. Clarity emerges through iteration, not avoidance.

- Premature optimization: Performance tuning too early restricts discovery. Early phases benefit from exploration. Optimization works best once behavior becomes clear.

These traps share one consequence: they limit learning before understanding fully forms. Avoiding them keeps exploration productive and preserves flexibility when decisions begin to matter.

Applying Parametric Thinking Beyond Architecture

Parametric thinking applies wherever systems change in response to input. Its value increases in fields that depend on scale, feedback, and evolving constraints.

Urban Systems and Infrastructure

Cities operate as layered systems. Traffic flow, density, energy use, and social behavior interact constantly. Parametric logic supports adaptable planning strategies that respond to growth, policy changes, and environmental data without full redesign.

Product, Fashion, and Digital Design

Products respond to user behavior. Fashion adapts to material performance and production limits. Digital platforms adjust through user feedback. Parametric thinking aligns well with these fields because rules scale, variation adds value, and feedback improves outcomes continuously.

When Parametric Thinking Adds the Most Value

Not every project needs a parametric approach. Its strength appears under specific conditions.

Projects benefit most when constraints remain uncertain, scale increases complexity, or performance matters as much as appearance. Early-stage exploration gains flexibility without committing to a single path. Systems with long lifespans benefit from adaptability as conditions evolve.

Parametric thinking does not replace design intuition — it supports it. Designers gain clarity, resilience, and confidence when complexity stops feeling like a threat and starts acting like structured information.